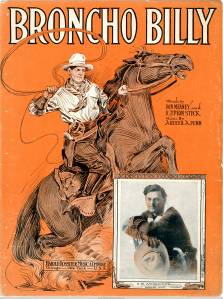

It was 1903, a time when Butch Cassidy & the Sundance Kid were still raiding from Devil’s Hole and Los Angeles itself not much more than a hole in the wall, that the one-reel western drama The Great Train Robbery scored a huge hit with audiences stirred by a life and time rapidly passing by. This was four years before a viable movie industry began in the United States, and a stage thespian and featured player from the short film, G. M. Anderson, formed the Essanay motion picture production company in Chicago and began his career as a cowboy on screen, namely “Bronco Billy”.

For a while, travelling “wild west” shows starring William “Buffalo Bill” Cody, Sitting Bull and others outdrew western movies for paying audiences. Wyatt Earp (still spry until 1929) volunteered himself as a historical-technical consultant to filmmakers, and the real west imposed itself on screen art too by incorporating real cowboys and Indians as stuntmen doubling as actors, some of whom became proto-stars. Enterprising small outfits, ever more mobile like American and Bison, set up filming units in the wilds of California before there was a Hollywood and used the raw resources at hand (including lead actor Francis Ford, brother of future director John Ford), making probably the most authentic westerns ever. Apaches grew more popular in France, then the centre of filmmaking, than they had ever been to Americans, white or red, and Star Film of Paris set up shop in Flagstaff, Arizona. Producer-director Gaston Melies, partner and brother of Georges Melies, one of the founding fathers of narrative film, was the local honcho, later joined in North America by leading continental European companies such as Pathe-Freres, Gaumont, Nordisk and independent Solax. The wilds of Fort Lee, New Jersey, close to the big film companies in New York, remained the mecca of western filmmaking until World War I.

It wasn’t until 1915 or so that the long, lean dramatic figure of the classic cowboy eclipsed the popularity of squat, energetic Bronco Billy with his pat heroics. While the stark, dressed-all-in-black William S. Hart was the new sensation in character-driven dramas promoted in the films from Paramount, the biggest studio and film distributor in the suddenly burgeoning Hollywood, at nearby Universal City rode dour Harry Carey directed by John Ford as saddle bum “Cheyenne Harry”, and Tom Mix, with experience as a wrangler and deputy sheriff, was making steady progress at Fox, perversely portraying a cowboy with spangles and shiny spurs and riding Tony the “wonder horse”.

Hart had earned massive fees of $150,000 and $200,000 per movie in a time of virtually no income tax; and gained such high prestige he was invited by Charles Chaplin, Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks to be a founding partner in United Artists (1919) before being substituted by D. W. Griffiths. Through the 1920s, though, Tom Mix set the tone by appearing in six to eight B-movies a year, said to earn $17,000 per week while filming, averaging out to a steady $7,500 a week through the years. Hoot Gibson came to emulate him at Universal, ousting the realism of the Ford-Carey films; as Fred Thomson did at FBO — Film Booking Offices, whose major shareholder was a certain Joseph P. Kennedy, lover of Gloria Swanson, before it morphed into the famous RKO studio at the beginning of talkies. These two also approached Mix’s commercial appeal, reportedly rewarded with during-filming weekly pay of $14,500 (Gibson) and $15,000 (Thomson). A last gasp try at A-movie status for westerns was pushed by MGM late in the decade through hero Tim McCoy appearing in a select few relative blockbusters with good co-stars and supporting casts.

Tom Mix retired from the screen, temporarily as it turned out, in 1930 when he was still riding high at 10th place in Quigley’s annual box-office survey, albeit through bulk product in release. Tiring of proving his credentials live in “wild west” travelling shows, he returned two years later, by which time Buck Jones and Jack Holt in B’s were the only cowboys showing up in the annual top 25 stars list. Buck continued scoring on his own up to 1935, multitudes of strictly B “stars” like Ken & Kermit Maynard, Charles Starret, Tom Tyler, Smith Ballew and Bob Steele lining up at tiny “Poverty Row” studios like Monogram, Grand National, Chesterfield and Tiffany; and aspiring Columbia and Universal. In 1930 the athleticism of Johnny Mack Brown had made a good impression in a big, realistic production of Billy the Kid at MGM, while John Wayne in his first major lead role was doomed by the failure of Fox blockbuster The Big Trail to a decade as a B-cowboy and the best part of another as a mediocre star before taken fully in hand by ace western directors John Ford and Howard Hawks.

The founding of Republic studio in 1935 would lead to singing cowboys Gene Autry and then Roy Rogers climbing to top 10 star status through appeal to undiscerning audiences unconcerned with authenticity with, again, bulk output. This trail was followed too by William Boyd as Hopalong Cassidy and led to the overwhelming popularity of kids’ cowboys on tv from 1949 through the early 1950s: The Lone Ranger, The Cisco Kid, Kit Carson, et al. It was a species John Wayne, best known on screen as gunslinger “Singing Sandy” in the mid Thirties, had only torturously escaped, handed a plum role in Stagecoach (1939) by Ford.

Henry Fonda broke through to major stardom — that top 25 published each year by the Motion Picture Herald — in 1939 and 1940 courtesy of western roles in Jesse James, Drums Along the Mohawk and The Return of Frank James, a status he couldn’t sustain in ensuing sophisticated comedies and then forestalled by war service that put him behind the eight ball. To cement his comeback he wisely chose Ford classics My Darling Clementine (1946) and Fort Apache (1948).

In the meantime, Gary Cooper, who’d made his name at the first death of westerns as talkies came in as laconic hero The Virginian and The Man From Wyoming, had made tentative steps to return as The Plainsman (1937) as Wild Bill Hickok and The Westerner (1940) under top directors Cecil B. DeMille and William Wyler. It was obvious the A-western was here to stay when odd-man-out Errol Flynn at Warner Bros, the studio of urban modernism, was, Tasmanian accent intact, diverted once a year from his pirate swashbucklers to depict the classic heroic westerner in an expensive and highly popular series from 1939: Dodge City, Virginia City, Santa Fe Trail, They Died With Their Boots On, San Antonio…By the end of World War II the main feature western at the Saturday matinee was such a staple that established routine stars Randolph Scott and Joel McCrea restricted themselves to the genre for the rest of their careers. McCrea made it among the runners at 23rd in 1950, while Scott (best directed by Budd Boetticher) was a fixture in the list from 1948 to 1956, top 10 the middle four years. By this time not only Gary Cooper was a regular in westerns, but James Stewart more popular than ever, re-entering the upper echelon after ten years, moreover joining his friend Coop in the top 10 for the first time (1951). While Stewart, mostly directed by Anthony Mann for Universal, got wealthy on percentage-participation deals, other Universal contractees on salary grew into big stars in westerns: Audie Murphy, Jeff Chandler, Rock Hudson.

Through the Sixties and into the Seventies, while John Wayne ruled tall in the saddle, other established stars extended their careers and broadened their appeal by going western: Gregory Peck, Burt Lancaster, Kirk Douglas, Robert Mitchum, Charlton Heston, Richard Widmark; and veteran supporting actors Lee Marvin, Charles Bronson, Lee Van Cleef morphed into bona fide stars. B-westerns were long gone from the big screen to tv series, developing Steve McQueen (Wanted: Dead or Alive), James Garner (Maverick) and Eastwood himself (Rawhide) into superstars.

Cowboys and American Indians have fared poorly on screen over the past forty years in the era of wookies and hobbits and other differently-normal humanoids. In 1965, after a decade when classic western tales ruled television, just as two admirably realistic series in Wagon Train and Rawhide folded after ‘long’ six-to-seven-years runs, new trends began innovating on the small screen: The Wild Wild West, The Big Valley, followed by Cimarron Strip, Lancer and The Outcasts. These, providing bright spots with their own flavor, were all gone by 1969 while the more traditional Bonanza and High Chaparral limped along for another couple or three seasons, and Gunsmoke out-gunned all the odds and broke the all-time record for a 20-year run into 1975.

That year saw Posse, produced by and starring Kirk Douglas, with a quirky anti-establishment take on western politics, but was isolated and muted in its impact amid ongoing efforts by John Wayne to mythologize “The West” while failing to match his Oscar-winning True Grit (1969). The jokey, indulgent taint purveyed into a staple of the big screen through the mid Sixties had descended by then to MacKenna’s Gold, Paint Your Wagon and Support Your Local Sheriff/Gunfighter. The feel-good, romantic thrust of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid the same year as these last two and Wayne’s landmark performance was more in the blockbuster tradition of Hollywood than the western one. It was in stark contrast to Sergio Leone’s contemporaneous Once Upon a Time in the West. Burt Lancaster through the early Seventies made a number of thoughtful contributions in Lawman, Ulzana’s Raid and Valdez is Coming, exploring the underbelly of history, along with Chato’s Land (Charles Bronson) — a worthwhile echo of Paul Newman’s Hombre the decade before. These, influenced to varying degrees by the “Spaghetti westerns” of director Sergio Leone (not forgetting the atmospheric music of Ennio Morricone), failed to ignite a new tradition for long in the States, aside from Eastwood’s ongoing thematic and stylistic tributes to his Italian mentor.

Mel Brooks’Blazing Saddles ripped the shit out of every cliche contained in what, up to then, had been thought ‘classic’ westerns. And two years later even stalwart Clint seemed to take the coming of Spielberg, Lucas and their acolytes to heart and The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976) was the last in his series of gritty oaters, reviving his ruthless man-with-no-name character only for isolated triumphs Pale Rider and Unforgiven over the following decade or two. That year too marked what should have been a classic on-screen meeting between Marlon Brando and Jack Nicholson in The Missouri Breaks, but wasn’t. Odd landmarks like Heaven’s Gate and Silverado came and went without threatening Clint’s monopoly. Only Tombstone (Kurt Russell – Val Kilmer), which put Kevin Costner’s Wyatt Earp in the shade, and Costner’s Dances With Wolves and Open Range made much of an impact afterwards. Cowboys met New Age, maybe sealing the lid on the genre’s coffin, in Brokeback Mountain.